Critical Analysis: Controversial Study Questioning Ozone Hole Recovery Faces Scrutiny for Flawed Data and Methodology

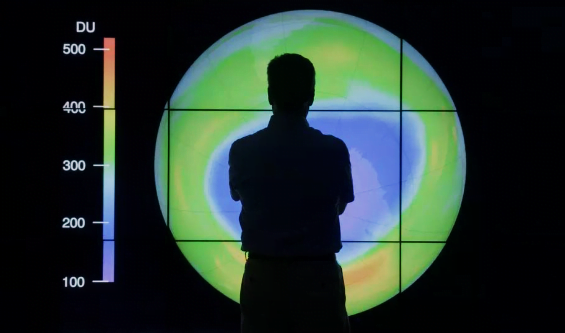

A recent study has raised concerns that the ozone hole above Antarctica might be deepening, suggesting a slower recovery than anticipated. However, experts not involved in the study dispute these claims, citing flaws in the research methodology.

The ozone layer, crucial for shielding life from harmful ultraviolet rays, has been under threat since the 1980s when chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) led to the emergence of ozone holes, particularly over the poles. The Montreal Protocol, implemented in 1987, globally phased out the use of CFCs.

Despite a reduction in the size of ozone holes, especially over Antarctica, persisting CFC levels and unpredictable climate conditions have hindered a complete recovery. According to a January United Nations report, pre-1980 ozone levels are expected to be restored by 2045 in the Arctic and 2066 in Antarctica.

However, a controversial study published on Nov. 21 in Nature Communications suggests a decrease in the concentration of ozone in Antarctica’s ozone hole. Media coverage asserting that the “ozone hole may not be recovering at all” has been criticized by experts who label the findings as dubious and misleading.

The study, analyzing ozone concentrations in Antarctica’s core from 2001 to 2022, claims a 26% average decrease. Renowned atmospheric scientist Susan Solomon challenges the study’s clarity and speculative nature. Notably, the paper fails to explain recent ozone decline factors, including La Niña, Australian wildfires, and an underwater eruption near Tonga in 2022.

Furthermore, the study omits data from 2002 and 2019, prompting skepticism. Critics argue that including these anomalous years would have provided a more comprehensive perspective. Atmospheric scientist Martin Jucker questions the study’s short time span, asserting that it overemphasizes recent years, yielding unrealistic results.

The study’s focus solely on the central ozone hole concentration, excluding broader ozone levels, is criticized by Solomon. Without models illustrating how central concentrations affect wider ozone levels, the study lacks comprehensive insights. Additionally, the choice of October and November data for maximum ozone hole size raises concerns, as September data could offer a more suitable baseline for assessing ozone recovery.

In conclusion, due to these oversights, the paper’s reliability in inferring global ozone recovery trends is questionable. For a more accurate understanding, it is crucial to consider a broader range of factors influencing ozone levels over time.